Reflections on Hillels of Florida Poland Trip

This winter break, I had the privilege of traveling to Poland with the Hillels of Florida. We walked through historic Jewish neighborhoods, learned about the vibrancy of Jewish life in Poland before World War II, and followed the paths of our own families as we bore witness to the atrocities at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, and Treblinka.

We began in Krakow, where our tour guide, Liz, helped us understand the depth and richness of Jewish life that once defined the country, and what was lost after the war. Poland has always felt inseparable from Jewish history for me because of its centrality to the Holocaust. But standing in Poland and seeing how little remains of what were once millions of Jewish lives and stories was deeply unsettling. The silence felt too heavy.

Before our next step, confronting the camps, we first encountered Jewish life as it exists today. We visited the Krakow JCC and explored the Jewish quarter, grounding ourselves in our connections to one another and to our people.

The first camp we visited was Auschwitz-Birkenau. While I studied the history of Nazi concentration and death camps growing up, nothing could have prepared me for seeing it in person. Walking through the camp, I was struck by the personal artifacts left behind — shoes, hair, and piles of belongings that once belonged to individuals whose lives were as complex as our own. That awareness multiplied itself over and over as we moved through the space.

The color-coded pots and pans, familiar to anyone who has been in a kosher kitchen, affected me deeply. Prisoners brought what little they could carry, holding tightly to Jewish tradition, even down to the details of their cookware, because it mattered to who they were. Many were led to believe they would return to their belongings after being disinfected. The calculated cruelty of the Nazis, exploiting that trust and persistence, is beyond understanding.

Among the many lies we confronted was the infamous phrase “work will set you free.” Standing at the gates, our conversation reframed it for me entirely. Of course it was a lie: no amount of labor could grant freedom. But in the work of maintaining faith, preserving memory, and believing even in the face of abandonment, people claimed a different kind of freedom, one rooted in spirit. We saw this in acts of resistance during the Holocaust, and we see it again today, among Israeli hostages who deepened their connection to Judaism in captivity.

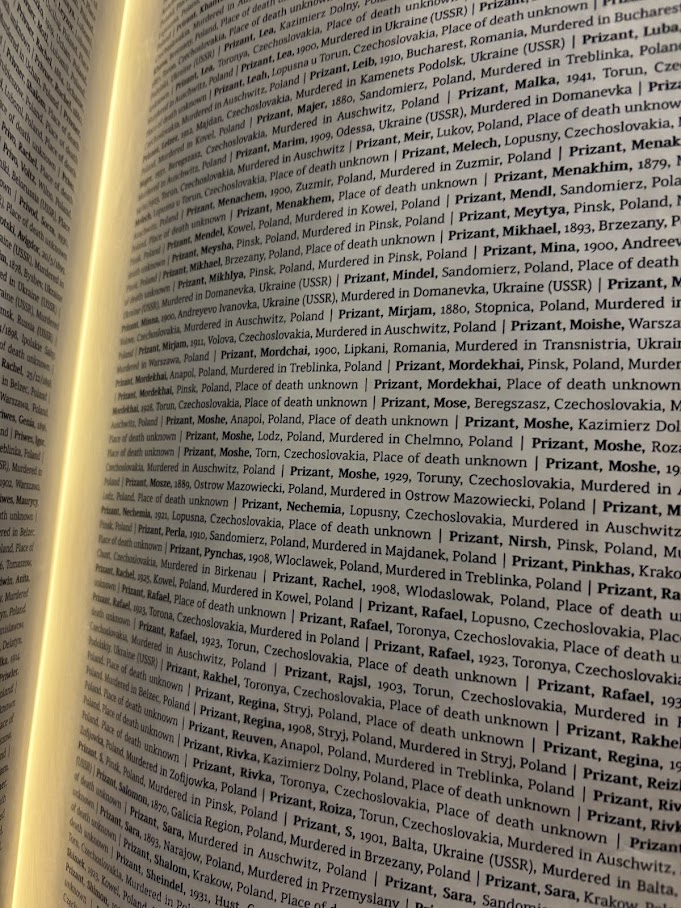

Inside Auschwitz, there is a book containing 4.5 million names of Holocaust victims. I did not have time to search for every branch of my family history, but I found three pages of victims with the surname “Prizant,” nearly identical to my mother’s maiden name, Prizont. My immediate family has no Holocaust survivors because they emigrated to Argentina or the United States decades before the war. Still, encountering those names unearthed a grief I did not know I carried. The book offered a glimpse into lives and stories I will never know because of the Nazis’ brutality.

I later spoke with a friend on the trip, Lea Visher, about wishing I had more time to keep searching. I wanted to see if I could find my grandmother’s maiden name, Wischñevsky, and learn more about what happened to her family. Lea then shared that her family’s original surname, changed only recently, was another variation of the same name. Unexpectedly, we realized that our family histories traced back to the same places. I do not believe in coincidences. Discovering that living connection at Birkenau, a site of immense loss, felt like an act of Jewish resistance. That evening, we lit a menorah together at Birkenau, singing and dancing as a community — living proof that the Jewish spirit endures.

The next camp we visited was Majdanek. I arrived knowing very little about its history, which made what we encountered even more difficult to absorb. The cruelty was staggering. Through the story of a 13-year-old girl named Helena — who had an attitude, idolized her older brother, and looked up to her mother — the enormity of the atrocities became deeply personal. We traced her journey through the camp as she saw her brother and mother for the last time before they were killed. Her story made clear that these crimes were committed against people just like us. Our people. About 18,000 Jews were murdered at Majdanek in the largest single-day, single-location massacre of the Holocaust, known as Operation Harvest Festival.

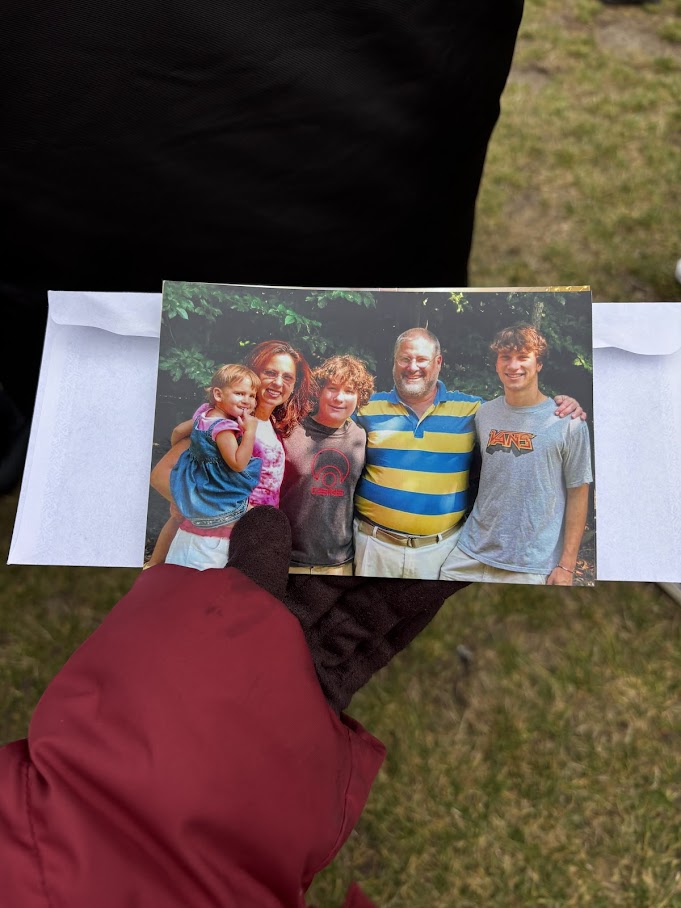

At the memorial, each of us held photos of our own families and reflected on who “made us Jewish” and what we carry forward from them. For me, it is my brother Max. His religious transformation before his sudden death continues to shape my faith. Max’s journey still inspires my own as I grow into years he never knew. Like Helena’s memories of her brother, and her grappling with the reality of outliving an older sibling, I understand that grief does not fade. It grows with us, and becomes part of who we are.

Standing there, family photos in our hands, I understood something deeply: Jewish people are made of one another. Collective memory is what keeps us — and through us, them — alive.

Our final site was Treblinka. Few people survived. Entire towns were erased. The Nazis destroyed nearly all physical evidence of the camp, leaving no buildings behind. In their place stands a field of 17,000 stones, marking the scale of the murder that occurred there in a single day. We walked silently among them, grappling with what each stone represented.

In Jewish tradition, each life is a world unto itself. We cannot comprehend the loss of six million worlds. But by visiting these sites, speaking names, and carrying stories forward, we ensure that those worlds are not forgotten. No one truly dies while their name is still spoken.

Amid the grief, we chose life. As one Hillel family, we held deep conversations, hugged without words, and danced late into the night. These moments of connection were sacred. This is the Jewish neshama, the soul, at its best. We move forward, carrying the light within us and living fully for those who were denied the chance.

I will carry these memories and bear witness to this history for the rest of my life as both a privilege and a responsibility. Since this trip, I have never felt prouder to be Jewish. It is the greatest gift of my life.